Abstract

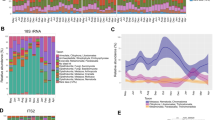

The host-associated microbiome affects individual health and behaviour, and may be influenced by local environmental conditions. However, little is known about microbiomes’ temporal dynamics in free-living species compared with their dynamics in humans and model organisms, especially in body sites other than the gut. Here, we investigate longitudinal changes in the fur microbiome of captive and free-living Egyptian fruit bats. We find that, in contrast to patterns described in humans and other mammals, the prominent dynamics is of change over time at the level of the colony as a whole. On average, a pair of fur microbiome samples from different individuals in the same colony collected on the same date are more similar to one another than a pair of samples from the same individual collected at different time points. This pattern suggests that the whole colony may be the appropriate biological unit for understanding some of the roles of the host microbiome in social bats’ ecology and evolution. This pattern of synchronized colony changes over time is also reflected in the profile of volatile compounds in the bats’ fur, but differs from the more individualized pattern found in the bats’ gut microbiome.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in this study has been uploaded to SRA at NCBI, and can be found under Bioproject PRJNA494618 (biosample accession numbers: SAMN10226814–SAMN10227267 and SAMN10174956–SAMN10175066).

References

Koch, H. & Schmid-Hempel, P. Socially transmitted gut microbiota protect bumble bees against an intestinal parasite. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19288–19292 (2011).

Sharon, G. et al. Commensal bacteria play a role in mating preference of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 20051–20056 (2010).

Vuong, H. E., Yano, J. M., Fung, T. C. & Hsiao, E. Y.The microbiome and host behavior.Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 40, 21–49 (2017).

Hooper, L. V., Littman, D. R. & Macpherson, A. J. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 336, 1268–1273 (2012).

Bravo, J. A. et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 16050–16055 (2011).

O’Mahony, S. M., Clarke, G., Borre, Y. E., Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain–gut–microbiome axis. Behav. Brain Res. 277, 32–48 (2015).

Forsythe, P., Bienenstock, J. & Kunze, W. A. in Microbial Endocrinology: The Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis in Health and Disease 115–133 (Springer, New York, 2014).

Foster, J. A. & Neufeld, K.-A. M. Gut–brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 36, 305–312 (2013).

Troyer, K. Behavioral acquisition of the hindgut fermentation system by hatchling Iguana iguana. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 14, 189–193 (1984).

Muegge, B. D. et al. Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science 332, 970–974 (2011).

Ley, R. E. et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science 320, 1647–1651 (2008).

Sanders, J. G. et al. Baleen whales host a unique gut microbiome with similarities to both carnivores and herbivores.Nat. Commun. 6, 8285 (2015).

Degnan, P. H. et al. Factors associated with the diversification of the gut microbial communities within chimpanzees from Gombe National Park. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 13034–13039 (2012).

Archie, E. A. & Theis, K. R. Animal behaviour meets microbial ecology. Anim. Behav. 82, 425–436 (2011).

Theis, K. R., Schmidt, T. M. & Holekamp, K. E. Evidence for a bacterial mechanism for group-specific social odors among hyenas. Sci. Rep. 2, 615 (2012).

Ezenwa, V. O., Gerardo, N. M., Inouye, D. W., Medina, M. & Xavier, J. B. Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science 338, 198–199 (2012).

Albone, E. S., Gosden, P. E., Ware, G. C., Macdonald, D. W. & Hough, N. G. Bacterial action and chemical signalling in the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and other mammals. In Flavor Chemistry of Animal Foods 78–91 (ACS Symposium Series Volume 67, ACS Publications, 1978).

Albone, E. S., Eglinton, G., Walker, J. M. & Ware, G. C. The anal sac secretion of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes); its chemistry and microbiology. A comparison with the anal sac secretion of the lion (Panthera leo). Life Sci. 14, 387–400 (1974).

Perofsky, A. C., Lewis, R. J., Abondano, L. A., Di Fiore, A. & Meyers, L. A. Hierarchical social networks shape gut microbial composition in wild Verreaux’s sifaka. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20172274 (2017).

Lax, S. et al. Longitudinal analysis of microbial interaction between humans and the indoor environment. Science 345, 1048–1052 (2014).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Moving pictures of the human microbiome. Genome. Biol. 12, R50 (2011).

Faith, J. J. et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science 341, 1237439 (2013).

Flores, G. E. et al. Temporal variability is a personalized feature of the human microbiome. Genome Biol. 15, 531 (2014).

Costello, E. K. et al. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326, 1694–1697 (2009).

The Human Microbiome Project Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207–214 (2012).

Oh, J. et al. Temporal stability of the human skin microbiome. Cell 165, 854–866 (2016).

Grice, E. A. & Segre, J. A. The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 244–253 (2011).

Grice, E. A. et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science 324, 1190–1192 (2009).

Bik, E. M. et al. Marine mammals harbor unique microbiotas shaped by and yet distinct from the sea.Nat. Commun. 7, 10516 (2016).

Ezenwa, V. O. & Williams, A. E. Microbes and animal olfactory communication: where do we go from here? Bioessays 36, 847–854 (2014).

Voigt, C. C., Caspers, B. & Speck, S. Bats, bacteria, and bat smell: sex-specific diversity of microbes in a sexually selected scent organ. J. Mammal. 86, 745–749 (2005).

Voigt, C. C. & von Helversen, O. Storage and display of odour by male Saccopteryx bilineata (Chiroptera, Emballonuridae). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 47, 29–40 (1999).

Theis, K. R. et al. Symbiotic bacteria appear to mediate hyena social odors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 19832–19837 (2013).

Theis, K. R., Venkataraman, A., Wagner, A. P., Holekamp, K. E. & Schmidt, T. M. in Chemical Signals in Vertebrates 13 87–103 (Springer, Cham, 2016).

Harten, L. et al. Persistent producer–scrounger relationships in bats. Sci. Adv. 4, e1603293 (2018).

Clayton, J. B. et al. Captivity humanizes the primate microbiome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10376–10381 (2016).

Nelson, T. M., Rogers, T. L., Carlini, A. R. & Brown, M. V. Diet and phylogeny shape the gut microbiota of Antarctic seals: a comparison of wild and captive animals. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 1132–1145 (2013).

Amato, K. R. Co-evolution in context: the importance of studying gut microbiomes in wild animals.Microbiome Sci. Med. 1, 10–29 (2013).

Kohl, K. D., Skopec, M. M. & Dearing, M. D. Captivity results in disparate loss of gut microbial diversity in closely related hosts.Conserv. Physiol. 2, cou009 (2014).

Kohl, K. D. & Dearing, M. D. Wild‐caught rodents retain a majority of their natural gut microbiota upon entrance into captivity. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 6, 191–195 (2014).

Lloyd-Price, J. et al. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature 550, 61–66 (2017).

Ayorinde, F., Wheeler, J. W., Wemmer, C. & Murtaugh, J. Volatile components of the occipital gland secretion of the bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus). J. Chem. Ecol. 8, 177–183 (1982).

Mattina, M. J. I., Pignatello, J. J. & Swihart, R. K. Identification of volatile components of bobcat (Lynx rufus) urine. J. Chem. Ecol. 17, 451–462 (1991).

Martín, J., Barja, I. & López, P. Chemical scent constituents in feces of wild Iberian wolves (Canis lupus signatus). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 38, 1096–1102 (2010).

Simpson, J. T., Weldon, P. J. & Sharp, T. R. Identification of major lipids from the scent gland secretions of Dumeril’s ground boa (Acrantophis dumerili Jan) by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Z. Naturforsch C 43, 914–917 (1988).

Soini, H. A. et al. Investigation of scents on cheeks and foreheads of large felines in connection to the facial marking behavior. J. Chem. Ecol. 38, 145–156 (2012).

Apps, P., Mmualefe, L. & McNutt, J. W. Identification of volatiles from the secretions and excretions of African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus). J. Chem. Ecol. 38, 1450–1461 (2012).

Khannoon, E. R. R. Secretions of pre-anal glands of house-dwelling geckos (Family: Gekkonidae) contain monoglycerides and 1,3-alkanediol. A comparative chemical ecology study. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 44, 341–346 (2012).

Kim, H. B. et al. Longitudinal investigation of the age-related bacterial diversity in the feces of commercial pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 153, 124–133 (2011).

Yatsunenko, T. et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 486, 222–227 (2012).

Mueller, N. T., Bakacs, E., Combellick, J., Grigoryan, Z. & Dominguez-Bello, M. G. The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends Mol. Med. 21, 109–117 (2015).

Lemieux-Labonté, V., Tromas, N., Shapiro, B. J. & Lapointe, F.-J. Environment and host species shape the skin microbiome of captive neotropical bats. PeerJ 4, e2430 (2016).

Avena, C. V. et al. Deconstructing the bat skin microbiome: influences of the host and the environment. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1753 (2016).

Winter, A. S. et al. Skin and fur bacterial diversity and community structure on American southwestern bats: effects of habitat, geography and bat traits. PeerJ 5, e3944 (2017).

Hicks, A. L. et al. Gut microbiomes of wild great apes fluctuate seasonally in response to diet. Nat. Commun. 9, 1786 (2018).

Smits, S. A. et al. Seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Science 357, 802–806 (2017).

Raulo, A. et al. Social behaviour and gut microbiota in red‐bellied lemurs (Eulemur rubriventer): in search of the role of immunity in the evolution of sociality.J. Anim. Ecol. 87, 388–399 (2017).

Tung, J. et al. Social networks predict gut microbiome composition in wild baboons. eLife 4, e05224 (2015).

Smith, I. & Wang, L.-F. Bats and their virome: an important source of emerging viruses capable of infecting humans. Curr. Opin. Virol. 3, 84–91 (2013).

Luis, A. D. et al. A comparison of bats and rodents as reservoirs of zoonotic viruses: are bats special?. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20122753 (2013).

Hayman, D. T. S. et al. Ecology of zoonotic infectious diseases in bats: current knowledge and future directions. Zoonoses Public Health 60, 2–21 (2013).

Calisher, C. H., Childs, J. E., Field, H. E., Holmes, K. V. & Schountz, T.Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses.Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 531–545 (2006).

Dietrich, M., Kearney, T., Seamark, E. C. J. & Markotter, W.The excreted microbiota of bats: evidence of niche specialisation based on multiple body habitats.FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364, fnw284 (2017).

Hoyt, J. R. et al. Bacteria isolated from bats inhibit the growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the causative agent of white-nose syndrome. PLoS ONE 10, e0121329 (2015).

Vanderwolf, K. J., Malloch, D. & McAlpine, D. F.Fungi on white-nose infected bats (Myotis spp.) in Eastern Canada show no decline in diversity associated with Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Ascomycota: Pseudeurotiaceae). Int. J. Speleol. 45, 43–50 (2016).

Blehert, D. S. et al. Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen? Science 323, 227 (2009).

Leopardi, S., Blake, D. & Puechmaille, S. J. White-nose syndrome fungus introduced from Europe to North America. Curr. Biol. 25, R217–R219 (2015).

Zilber‐Rosenberg, I. & Rosenberg, E. Role of microorganisms in the evolution of animals and plants: the hologenome theory of evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 723–735 (2008).

Theis, K. R. et al. Getting the hologenome concept right: an eco-evolutionary framework for hosts and their microbiomes. mSystems 1, e00028-16 (2016).

Dinsdale, E. A. et al. Functional metagenomic profiling of nine biomes. Nature 452, 629–632 (2008).

Gill, S. R. et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 312, 1355–1359 (2006).

Doolittle, W. F. & Inkpen, S. A. Processes and patterns of interaction as units of selection: an introduction to ITSNTS thinking. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4006–4014 (2018).

Moran, N. A. & Sloan, D. B. The hologenome concept: helpful or hollow? PLoS Biol. 13, e1002311 (2015).

Dugatkin, L. A. & Reeve, H. K. Behavioral ecology and levels of selection: dissolving the group selection controversy. Adv. Study Behav. 23, 101–133 (1994).

Gould, S. J. & Lloyd, E. A. Individuality and adaptation across levels of selection: how shall we name and generalize the unit of Darwinism? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 11904–11909 (1999).

Tedman, R. A. & Hall, L. S. The morphology of the gastrointestinal tract and food transit time in the fruit bats Pteropus alecto and P. poliocephalus (Megachiroptera). Aust. J. Zool. 33, 625–640 (1985).

Utzurrum, R. C. B. & Heideman, P. D. Differential ingestion of viable vs nonviable Ficus seeds by fruit bats. Biotropica 23, 311–312 (1991).

Zhang, J., Kobert, K., Flouri, T. & Stamatakis, A. PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics 30, 614–620 (2013).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2409v1 (2016).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Letten, P.-J. Ke, M. Donald, N. Dudek, W. Van Treuen, L. Costello, M. Maor, T. Simon and E. Ebel for technical help and insightful comments. O.K. is supported by the John Templeton Foundation and Stanford Center for Computational, Evolutionary, and Human Genomics. This research was partially supported by the European Research Council (ERC–GPSBAT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.K., M.W., L.R. and Y.Y. planned the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.W., L.R. and L.H. collected and processed the samples. All co-authors commented on the study design, data analysis and manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information Sections 1–8

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kolodny, O., Weinberg, M., Reshef, L. et al. Coordinated change at the colony level in fruit bat fur microbiomes through time. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 116–124 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0731-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0731-z

This article is cited by

-

A computational framework for resolving the microbiome diversity conundrum

Nature Communications (2023)

-

The Mycobiome of Bats in the American Southwest Is Structured by Geography, Bat Species, and Behavior

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

Microbial isolates with Anti-Pseudogymnoascus destructans activities from Western Canadian bat wings

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Consistency of Bacterial Communities in a Parasitic Worm: Variation Throughout the Life Cycle and Across Geographic Space

Microbial Ecology (2022)

-

Synchrony and idiosyncrasy in the gut microbiome of wild baboons

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022)